Saucy Jacky

Dear Boss

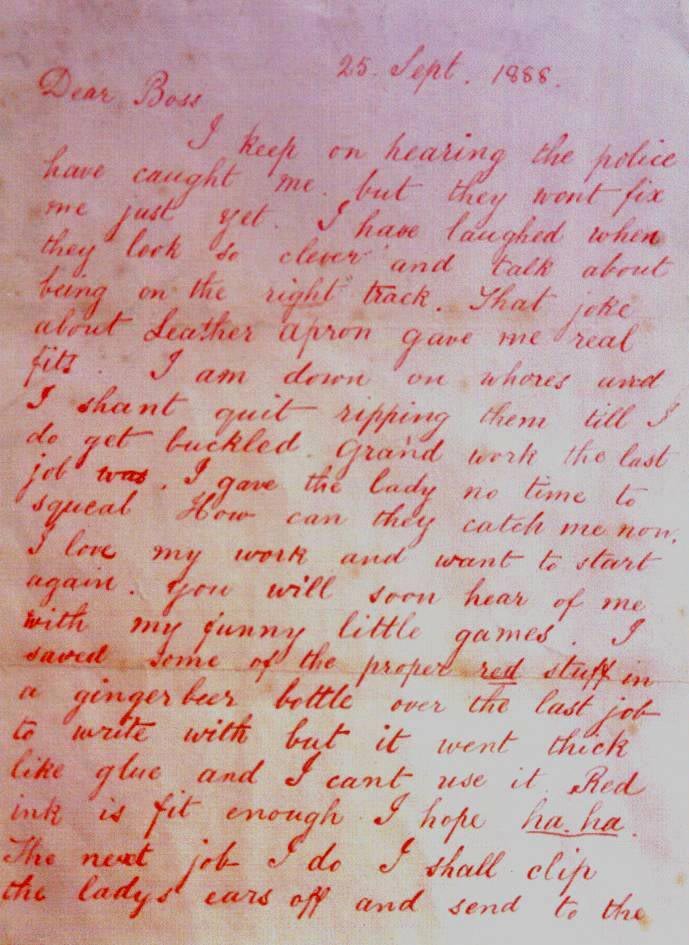

Page 1 of the Dear Boss Letter

The Dear Boss Letter

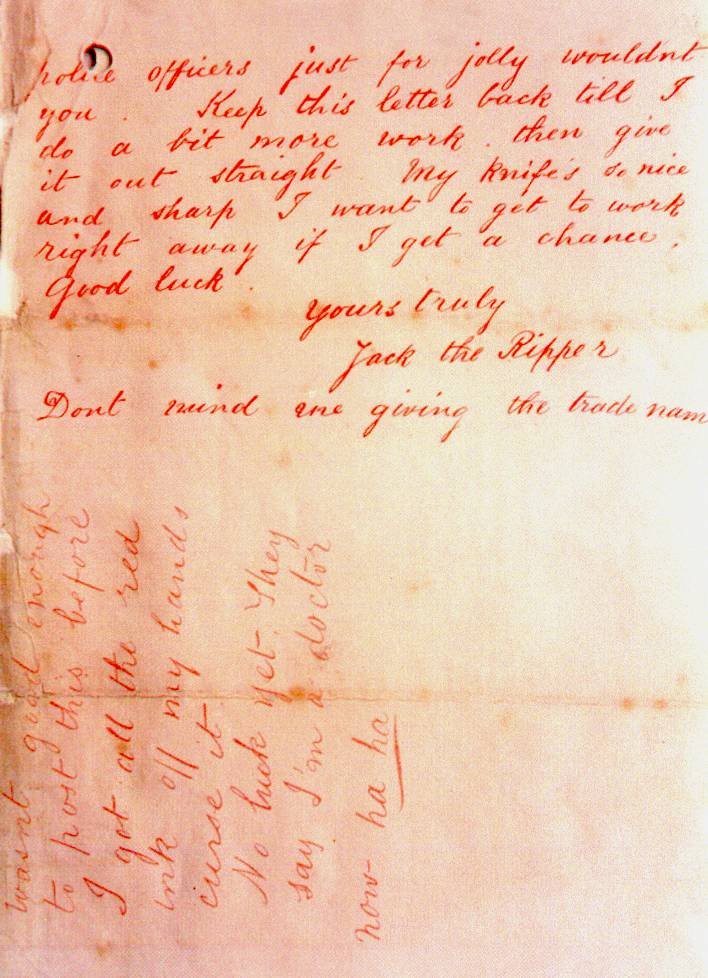

Page 2 of the Dear Boss Letter

The ‘Dear Boss’ letter was two pages long, written in red ink, and contained several spelling and punctuation mistakes. The letter mocked the police and indicated further murders would follow. The letter read:-

25 Sept, 1888

Dear Boss,

I keep on hearing the police have caught me but they wont fix me just yet. I have laughed when they look so clever and talk about being on the right track. That joke about Leather Apron gave me real fits. I am down on whores and I shant quit ripping them till I do get buckled. Grand work the last job was. I gave the lady no time to squeal. How can they catch me now. I love my work and want to start again. You will soon hear of me with my funny little games. I saved some of the proper red stuff in a ginger beer bottle over the last job to write with but it went thick like glue and I cant use it. Red ink is fit enough I hope ha. ha. The next job I do I shall clip the ladys ears off and send to the police officers just for jolly wouldn’t you. Keep this letter back till I do a bit more work, then give it out straight. My knife’s so nice and sharp I want to get to work right away if I get a chance. Good Luck. Yours truly

Jack the Ripper

Dont mind me giving the trade name

PS Wasnt good enough to post this before I got all the red ink off my hands curse it. No luck yet. They say I’m a doctor now. ha ha

The author sent the ‘Dear Boss’ letter to the Central News Agency in London rather than the police. Many investigators find that significant, as few outside the newspaper game knew of the organisation’s existence. If the letter writer wanted to bypass the police in favour of the press, the obvious choice was a prominent metropolitan newspaper such as the Star or the Times—not an obscure news service. Many researchers have accepted the letter as a journalistic hoax based on this fact alone.

The Agency received the letter on 27 September 1888 and forwarded it to Scotland Yard on 29 September. Initially, the Agency treated the letter as a hoax and ignored it; after further consideration, they decided to err on the side of caution and sent it to the police.

Like the News Agency, the police considered the letter just another of the many hoax letters purporting to be from the murderer. The police began to take the letter more seriously following the night of the ‘double event.’

The ‘killer’ who wrote the letter said he would cut off the ears of his next victim and send them to the police for a laugh. When the Whitechapel killer attacked Catherine Eddowes in Mitre Square on 30 September, he severed her right ear lobe. While it wasn’t the same as ‘clip[ping] the lady’s ears off’, it was close enough for the police to take the letter more seriously.

The Metropolitan Police circulated numerous handbills containing facsimiles of the letter and the “Saucy Jacky” postcard in the hope that a member of the public would recognise the handwriting. Some local and national newspapers printed some—or all—of the text of the “Dear Boss” letter. However, these efforts failed to generate any significant leads.

Following the publication of the ‘Dear Boss’ letter and the ‘Saucy Jacky’ postcard, the story went viral, and the Whitechapel murders gained worldwide notoriety. Whether the letter and card were hoaxes or not did not matter: The name ‘Jack the Ripper’ captured the public’s imagination, turning the tawdry murder of five or more destitute, part-time prostitutes into a cultural phenomenon. Almost one hundred and forty years later, Interest in the Whitechapel murders remains strong and has increased rather than diminished.

Like many Ripper-related documents, the “Dear Boss” letter disappeared not long after the police ended their investigation of the murders. Most people assumed one of the investigating officers had souvenired the letter.

The person in possession of the letter returned it to the Metropolitan Police anonymously in November 1987., Scotland Yard has now recalled all documents relating to the Whitechapel Murders from the Public Record Office, now called The National Archives.

In 1931, a journalist named Fred Best reportedly confessed that he and a colleague at The Star newspaper, Tom Bullen, had written the ‘Dear Boss’ letter and the ‘Saucy Jacky’ postcard to maintain interest in the story and generate higher sales. Believe it or not!

Talk to us

Have any questions, observations or suggestions? We would love to hear from you.